Machi Koro Video Game

During my summer break from college in 2017, I created a video game version of the board game Machi Koro using the Unity game development engine.

About the board game

Machi Koro is a board game where players build towns and try to raise enough money to build all 6 of the game’s historical landmarks in their town - at which point, they win the game.

Players make money through the businesses they build in their town: each has a set of dice rolls they activate on, and each business earns the player money in different ways. There are four types of businesses, and the type determines a business’s basic attributes:

- Green businesses activate when you roll their number(s)

- Blue businesses activate when anyone rolls their number(s)

- Red businesses activate when other players roll their number(s), at which point you steal coins from them, and

- Purple businesses also activate on your roll like green cards, but each have highly unique effects

Each player starts with 2 businesses, and purchases more through a marketplace selling 10 different businesses at a time, generated from drawing cards from the deck. As players earn more money, they can buy more businesses, which in turn allow them to earn money more quickly and purchase landmarks before everyone else.

Certain sets of businesses have effects that build on top of each other, and there is strategy in choosing which ones to pair together. There are some businesses that also counter other players’ setups, so one has to be able to adapt to the actions of the other players as well!

Making a video game recreation

Machi Koro was my first large-scale software project - creating it took roughly 100 hours of work.

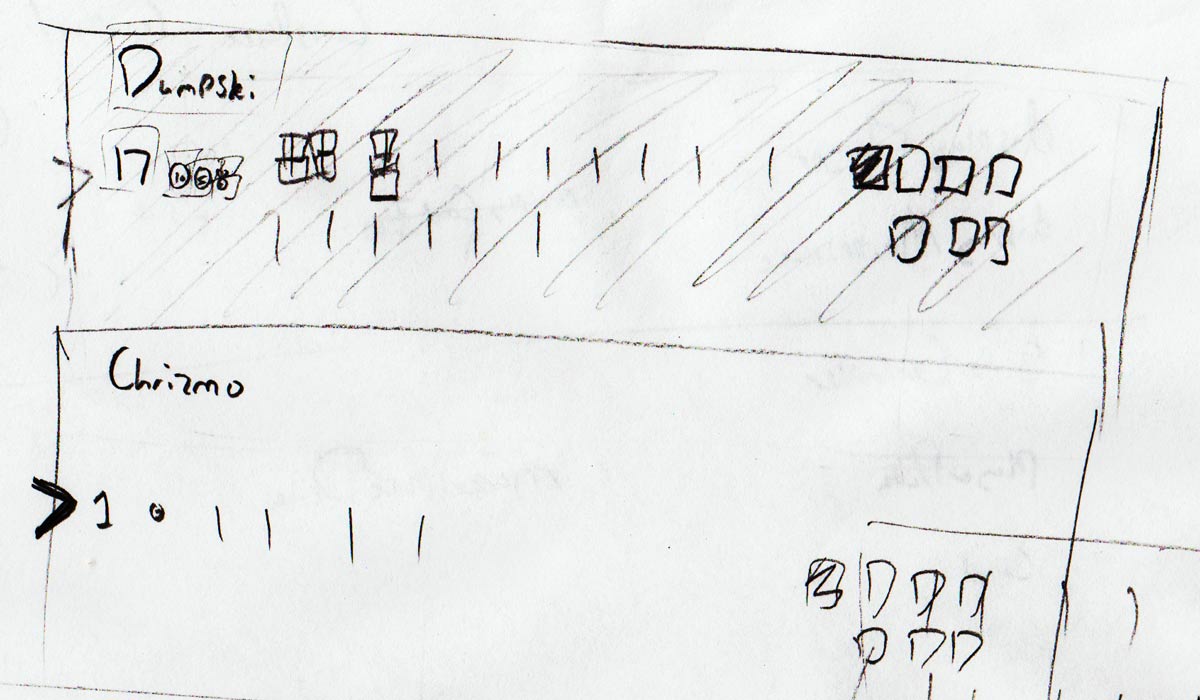

I started by creating UI mockups and outlining how objects in the game would be represented in the code.

The first work I did included getting all of the game’s visual assets into the game. I made scans of all of the cards and then cleaned each one up Photoshop. (I would have preferred to batch-process them, but the nature of my inexpensive scanner required some hand-edits on essentially every card.) I recreated the coins in Illustrator, as their design was fairly simple, and recreating them resulted in a cleaner asset than a scan could give. Finally, I chose two free fonts that felt reminiscent enough of the game’s own to display all of the text - one for the player’s stats, and another for everything else.

From there, I began creating the game’s objects using my earlier drafts, and getting Unity to properly associate related pieces (such as a player and their cards) and display them.

During this process, I began programming the logic that handles the different components of the game flow, including a turn and its individual pieces (such as rolling dice, buying a card, etc.), as well as the code that displays the changes that occur as this logic modifies in-game data. This made up the core of the project - once the game could play out in-full and display properly, development would essentially be finished.

The project neared completion just as the fall semester at my university was about to begin. During the last several days of development, I started keeping track of what I wanted done on a day-by-day basis.

The project was ultimately finished two days before school started. It needed some live testing with other players, but I had run through tests of all of the edge cases that I could think of and, most importantly, every feature that needed to be implemented to have a full recreation of the game and a solid user experience was complete.

Technical highlights

Developing the game helped solidify my understanding of object-oriented programming. I had to determine how to best represent the various components of the game - including the players, the marketplace, and the cards - in objects in the code.

Of particular challenge was the implementation of card actions. While cards shared some common attributes, the way in which they dealt money still varied on both a type-by-type basis and, quite regularly, a card-by-card basis. The section of the game loop that handles the calculation of earnings based on what cards are on the board simply calls for each card’s action when appropriate - the cards themselves define how to respond based first on their type, and then their individual constraints if needed. This overriding of default behavior is an example of a concept in computer science called polymorphism, where objects of different types can be accessed in the same way (in essence, as though they are the same type), but have different implementations, reacting differently even though the code attempting to access them is the same.

This project also introduced me to handling GUI events through the use of a game loop, a nearly-universal design pattern in video games used to handle the multitude of events that should happen on a frame-by-frame basis, such as polling for user input and rendering data changes to the screen. (I made some common beginner mistakes in handling game loops that I had to learn from - more in this in the next section.)

Lessons learned

As this was my first large-scale project, I made a number of mistakes that I learned from along the way. As the project size became fairly large, and the code base more difficult to handle as a result, I discovered several design patterns frequently utilized in video games.

Perhaps the most consequential design mistake I made - and one that could be solved through the use of a design pattern - was not handling management of program flow through the use of a finite state machine.

A finite state machine is a system that requires an object to have a state associated with it. The object can only be in one state at a time, and the state system defines a set of conditions under the object can change its state.

(For the curious: here’s the fantastic primer on handling state in video games that introduced me to the concept.)

Here’s why handling the game’s program flow through state management would have made the code in this project much cleaner:

Every turn in the game can be broken down into several components:

- rolling dice (and handling landmark effects related to rolling)

- handling any card actions that require user input

- choosing what card to buy (if any), and

- handling any post-turn effects caused by landmarks

During each of these states, certain actions should not be possible - for example, it shouldn’t be possible to buy a card while rolling dice. I learned the hard way that I should have managed this through keeping track of what state the program is in, and have actions fire only if the game state allows them to.

Instead, I used coroutines, functions that can pause their execution if a condition has not been met and return to it later. This resulted in code that is difficult to maintain, as there is no centralized definition of what should be able to happen when. (This appears to be a common ‘gotcha’ for Unity users who are beginners to GUI-based development: Unity makes the use of coroutines easy, and they’re usually the first solution beginners find to handling problems involving state.)

Results

While I can’t release the game or its source code publicly due to not owning the copyright, I still regularly play the game privately with friends. It’s particularly useful now that my friend group is spread out across several different locations - so long as I can share my screen via a video call, I can play with others through showing them the board and enacting their choices on their behalf.

I built the game as an enjoyable way to learn Unity and software development, but I also built it to have something that I could play online with a friend of mine who isn’t able to afford a particularly good Internet connection. (The only other games we could play were the Jackbox Party Pack games and competitive Pokémon through Pokémon Showdown… which I am very bad at!)

It’s helped bring a friend group of mine together despite distance, and also made my friends much more interested in Machi Koro. Considering the skills I learned and how enjoyable and useful the end product has been, I definitely feel it was a success!